The study “Excavating the English-Language Press in the Ottoman Empire (1841–1923) Editors, State Actors, Readers” by Stéphanie Prévost from Université de Paris sought to investigate a phenomenon thought to be almost nonexistent – English-language press in the Ottoman State.

The previous research on foreign-language press in the Ottoman Empire has focused on French. A total of 400 French press titles were published between 1795 and 1923 (Gérard Groc and Ibrahim Çağlar 1985). The French dominance was due to the fact that the Europeans who had settled in the Levant were francophones. Interest in polyglossia in the Empire only began in the 2010s, with the study by the author building on a study in 2020 by Burhan Çağlar investigating The Levant Herald.

The focus here is, rather than building a history of the press, is on appraising the language value and flexibility of the English-Ottoman titles. The study does this by looking at two main open access digital collections of foreign-language Ottoman publications. The collections are The ARIT-I Digital Library by American Research Institute in Turkey and The Bibliothèques d’Orient.

Three digitized titles include substantial sections in English: The Levant Herald (1856–1914); The Levant Times and Shipping Gazette (1868–1874) and successive titles Le Progrès d’Orient (1874)/ Le Stamboul (1875–1914); and The Oriental Advertiser/ Le Moniteur Oriental (1882–1920), These form the core of the English-Ottoman press.

Flexi-bilingualism was conspicuous in titles like The Levant Times and Shipping Gazette and The Oriental Advertiser. This meant opting for both French (to address the established readership in the Levant) while also publishing in English to pursue international recognition.

Mostly nationality was dissociated from language, with The Orient News being a notable exception, being established in the 1919 by Harry E. Pears as a British counterpoint to French language propaganda series.

The press also had to contend with the authorities and outright censorship. It bears remembering that English was seen as more suspicious foreign language than French. An emblematic example of this was seen in Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad (1869) that showed a drawn picture of an Ottoman censor reading The Levant Herald with the intention of censoring it.

The censorship increased in the 1860s with the controversial, British-opposed first Ottoman press law in 1864. It required a copy of each serial to be sent for inspection and possible censorship to the Press Bureau.

The scrutiny of particularly British newspapers increased when tensions heightened between the British government and the Ottoman Empire starting from 1867. This resulted rather counterintuitively not in an unified front by the papers but increased competition. The censorship finally reached its zenith during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876–1909), with some suspecting that the English-language press only survived due to being at the beck and call of the government – but they still managed to establish an independent editorial line.

All in all, the article serves as a point of evidence generally in how English-language titles in general function, not just in the Ottoman Empire but elsewhere too. It is also an important contribution to the archeology of English-language titles that media historians are seeking to uncover.

The article “Excavating the English-Language Press in the Ottoman Empire (1841–1923) Editors, State Actors, Readers” by Stéphanie Prévost is in Media History. (free abstract).

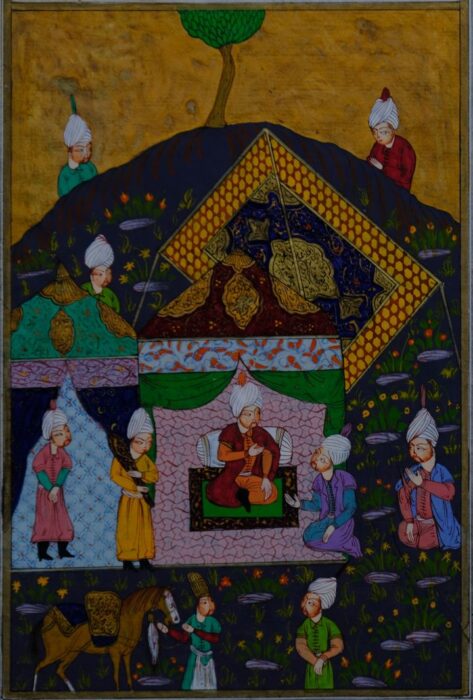

Picture: Hand-painted illustration from probably a book about Islam. Most likely well over 100 years old. by Boudewijn Huysmans

License Unsplash.